Pi Labs, a leading PropTech investor in Europe has published a comprehensive, very thorough white paper on what are the current barriers to deliver transparent and accurate ESG performance data and how to overcome them. As ESG funds are increasing their share of the European fund sector from 15% to 57%, experts claim that this trend is the biggest investment opportunity in the history of mankind!

And the companies that improve their approach to ESG data will be the ones to benefit from the new capital opportunities.

- A global catastrophe may it become

- Governance problems on the horizon

- Governments trying to shed some light

- A Benchmark Chaos We Call It

- Difficulties in data extraction

- The void in value drivers

- A new era for ESG performance evaluation and sustainable innovations

- Use cases and new ESG performance benchmarks

A global catastrophe may it become

Environmentally, real estate is faced with one of the biggest challenges of our time – how to decarbonise the existing building stock by the 2050? It has been widely reported that between 70 and 90% of the buildings that will be in use by the 2050 deadline have already been built. As only between 0.4-1.2% of the building stock in European countries are renovated yearly. Simple maths tells us that this retrofit rate needs to triple if we want to reach our climate goals.

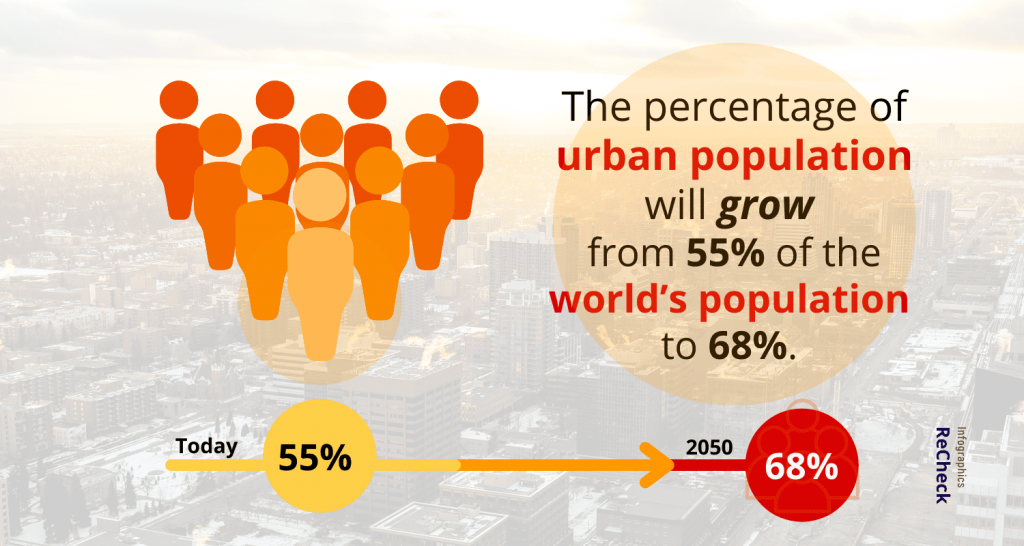

Then the UN predicts that the world’s population will double by 2050, with 90% of this growth to occur in Africa and Asia. In the same time, the percentage of urban population will grow from 55% to 68%. That is 2.5bn more people who will require shelter, heat, water and electricity.

Together, India, China and Nigeria will account for 35% of the projected growth and around 70% of the building floor area additions by 2050 will take place in areas with no, or very limited building energy strategy and agendas in place.

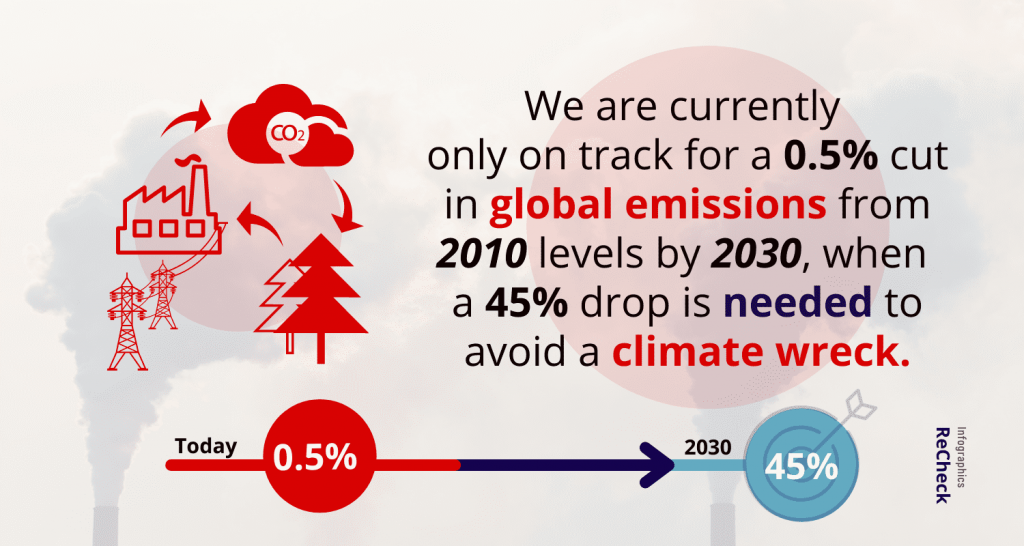

In fact, we are currently only on track for a 0.5% cut in global emissions from 2010 levels by 2030, when a 45% drop is needed to avoid a climate wreck.

Governance problems on the horizon

Currently, decisions in real estate are mostly based on expected short term financial returns and rest on very limited data. Basically, the industry continues to develop property on a speculative basis. Pension funds and investment managers will usually hold assets from 5 to 7 years before they sell it, in order to avoid the need to refurbish the property or otherwise suffer obsolescence.

Usually the facilities manager’s only point of contact with the buildings occupants is through the occupier’s HR team. And the problem with that is that HR teams often have very little information of how their spaces are used beyond what is learned from email complaints and room booking requests. If such data does exist, it is often held in paper-based format and is privately owned by the organisations who originated it.

At the same time, two thirds of real estate investors are looking to increase their allocation to ‘sustainable properties’. The new investor demand along with the tougher regulations and new financing initiatives has made the real estate industry look and re-evaluate their poor ESG performance. Assets with low scores will suffer low returns and non-financial performance in areas such as resource consumption and occupant wellbeing, when these are now becoming more traditional, financial metrics.

Governments trying to shed some light

There is significant confusion around how the real estate industry benchmarks and rewards ESG performance. The plethora of competing frameworks and standards makes it difficult to identify what makes a good ESG performance.

Many global investment managers have chosen to use the Financial Stability Board’s Task force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) framework for ESG reporting. Additionally, the EU regulation on Sustainability-Related Disclosures took effect on March 10, 2021. It requires from investment managers to disclose sustainability risks surrounding their investments. Likewise, the U.S. investors are preparing for identical regulations regarding carbon emissions and other sustainability metrics to be implemented.

The current EU taxonomy provides a framework for determining which investments are environmentally sustainable, but there is little focus on the social and governance factors, while the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation defines ‘sustainable investments’ with reference to the full ESG factors.

Organisatitons are finding that such disparity in regulations is creating operational challenges in aligning their businesses with the both pieces of regulation. And all this can lead to creating a market skewed towards investments with strong environmental performance as opposed to strong social and governance credentials.

Regardless of the current efforts and initiatives, the benchmarking of ESG investments and the metrics used to measure ESG performance in real estate have not yet matured enough. In this situation, real estate companies will often align their goals with one of the 20 mainstream standards that are currently in use. Furthermore, they usually hire external consultants to help with the complex and time-consuming ESG reporting.

The most recognised of these standards is GRESB (the Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark). However, its coverage is said to be far from comprehensive. While the global real estate industry is estimated to be valued at $217tn, those 1229 portfolios which report to GRESB represent some $4.8tn value of assets, representing 2% of all global real estate.

Unfortunately, the reporting process is quite confusing, as there are various initiatives competing to be the market leader by differentiating their approach to ESG reporting. A 2019 study by the MIT Sloan School of Management found that ESG ratings from five different providers coincided only 61% of the time. Furthermore, individual rating providers are commonly found guilty of ongoing re-writes to their historical ESG data.

In the end, all this makes the true ESG risk profile of assets almost impossible to complete. Aggregate ESG scores are common, but vague and hard to understand. Investors need to be aware if there are any variations, as these can result in very different outcomes using the same set of raw data.

A Benchmark Chaos We Call It

Due to the potential for a winner-takes-it-all market for whomever can provide the most comprehensive, reliable and compliant ESG dataset, rating organizations are reluctant to agree on a single open standard. Recently, the World Bank’s Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility called in all the major standards providers with a view to a greater standardisation of ESG benchmarks. Obviously, governments need to take a lead.

The GRESB and TCFD frameworks are often criticised for basing the ESG performance on the strength of an organization’s reporting rather than using the right source data. Further confusion occurs as GRESB is said to be giving some preferential treatment to certain ESG factors over others. This lead to reporting become susceptible to “greenwashing”. GRESB should give more attention to quantitative data evidence over qualitative statements in order to remain objective.

Inevitably, this subjective reporting favours property owners who are better resourced to report, giving rise to a number of sustainability consultancies who promise to maximise ESG accreditation and help with regulatory hurdles. While these consultancies can undoubtedly aid the non-financial performance of individual real estate organisations, they also benefit from the lack of transparency around reporting structures.

Globally, there are over 600 standards for certifying a vast array of asset-level ESG attributes – with over 100 of these in the US alone. Asset-level sustainability certifications include the well-known EPC, BREEAM, LEED and WELL ratings, with the latter focusing more on the wellbeing of occupants than the energy performance of the asset.

Those assets which score highly on these benchmarks are deemed to be market-leading and they lease faster than non-accredited assets. Furthermore, In the UK, starting from 2030, commercial landlords will be unable to renew tenancy agreements or create new tenancies if their EPC rating is B or lower. Buildings labelled as ‘more energy efficient’, with an EPC rating of A or B, now have 10% higher average rents in central London.

The design vs. operational paradox

The Better Building Partnership in the UK has found out that there is no correlation between a commercial asset’s Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating and its operational energy consumption. In reality, it turned out that buildings with different EPC ratings exhibited similar median energy consumption and a similar range of energy usage across each EPC band that was observed.

Actually, on average buildings perform 3.8 times less efficiently in operation than intended at design – there is a ‘performance gap’. This happens because accreditation is mostly based on single-point-in-time measurements, as opposed to real time, operational data. Evidence exists of an asset awarded a BREEAM sustainability rating of ‘Excellent’ at completion consuming 10 times more energy in operation than when it was assessed and accredited.

Difficulties in data extraction

Pi Labs reports that under most UK commercial lease structures, the tenant has no legal obligation to disclose energy consumption data to the landlord. And so, the energy efficiency metric most often reported refers to the common areas within the landlord’s property and not that of the full building.

Gensler’s Workplace Performance Index and the Leesman Index target the occupying user and are anonymised at the building level. However, even if such social sustainability measures such as workplace satisfaction are present, this information is not available to the managers of assets for further decision-making.

As there is a lack of clearly defined rules in the real estate industry for what biometric and personal data is allowed to be collected and how it is used, this blocks the use of occupancy monitoring technology by landlords which could otherwise improve both the environmental and social sustainability of an asset.

Occupancy monitoring, facial recognition and biometric data from wearable devices could all be used to enhance the wellbeing, safety and productivity of individuals. However, there is a huge data privacy concern that needs to be addressed.

Further ESG data disruption occurs at the point of each subsequent sale of a building. This happens because builders, developers and owners of buildings are not required to share design or operational consumption data. And such data could be used to improve future asset performance under the new ownership.

Additionally, almost half of CRE teams do not have the appropriate software or technical capabilities to check or upload any information which is provided to them by the design and construction teams.

An overwhelming majority of buildings in use are not digitally equipped to deliver data driven operational insights, and extraction still relies on manual meter readings or self-reported surveys.

Firms are finding that ESG information on the same company commonly differs, depending on which data provider is used. Despite investment managers providing 67% more ESG related data to investors, they are still failing to meet investors’ demands for greater information.

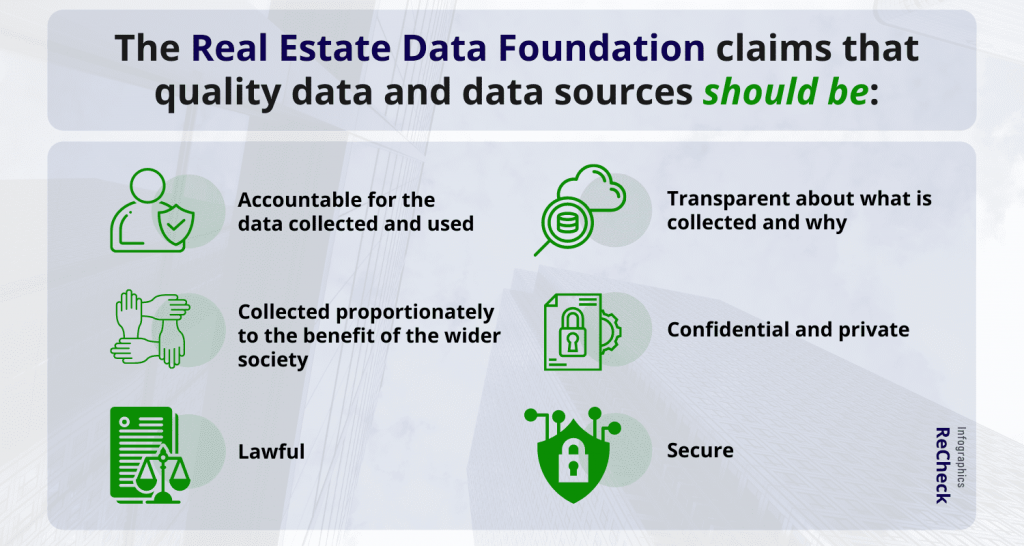

The Real Estate Data Foundation defines that quality data and data sources should be:

- Accountable for the data collected and used: This includes taking responsibility for using the data in an appropriate and secure way;

- Transparent about what is collected and why: While this cannot be expected for every data point, at a minimum a general data policy should be published for each building explaining what is collected and why;

- Proportionate: Not only should data be collected within legal and technical requirements, but is also proportionate to the benefit of the wider society;

- Confidential and private: All activity with data should at all times consider the confidentiality and protect privacy;

- Lawful: All data should only be used within relevant local and international laws and regulations;

- Secure: Security principles should be built in ‘by design’ into all applications and appropriate steps should be taken to keep data secure;

The void in value drivers

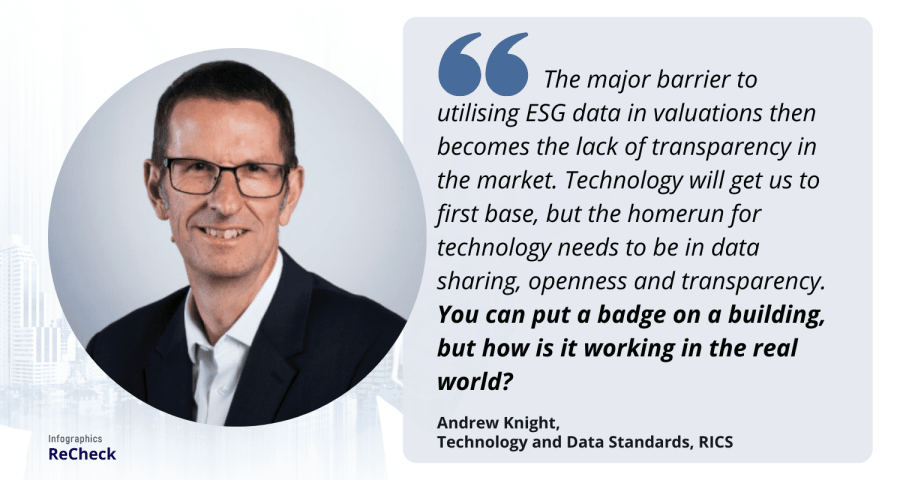

With 20 mainstream, non-transparent and subjective ESG reporting standards, it is no wonder that challenges exist when attempting to obtain comprehensive, comparable market level ESG data.

Indeed, most real estate ESG literature cites best practice case studies and one-off examples, with very little aggregated insight currently available. When Pi Labs contacted GRESB with a request for data, they revealed that they do not collect any information on the adoption of technology, or design data that could be used to examine the drivers of ESG performance for the benefit of the industry.

However given the scale of the remaining ESG issues and the emergence of new technologies, many legacy certifications are no longer fit for purpose and the industry must now increase its transparency beyond publishing subjective, single moment-in-time, aggregated third-party scores.

The data transparency issue is further aggravated by the heterogeneity of assets, which makes comparison difficult. At the same time, the impact of poor asset operation on ESG performance often nullifies any efficiencies brought about through technology.

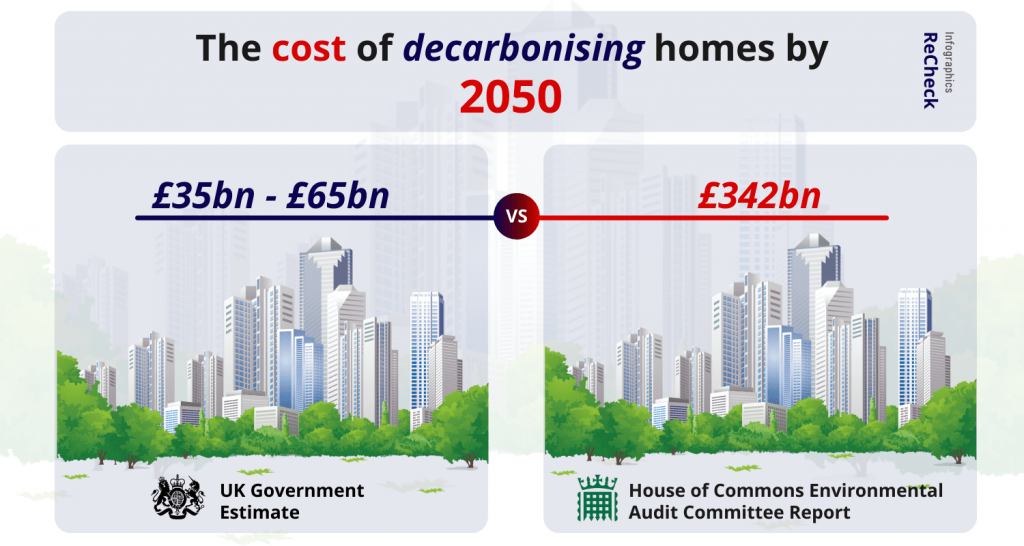

Then, the lack of details regarding the particular steps needed to increase energy performance is also threatening to suppress the much-needed investment. Using available data, the UK Government had estimated that the cost of decarbonising homes by 2050 was somewhere between £35bn and £65bn. However, analysis of this figure revealed it had overlooked the individual challenges of many properties. In the end, the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee (EAC) estimated this cost to be £342bn, an underestimate of £307bn!

The void in value drivers due to the lack of ESG data transparency is claimed to be the biggest barrier facing the real estate industry as it looks at how to improve its ESG performance. The intangible benefits of green certificates or carbon emission reductions, while important motivators for property investors have so far been ignored in valuations as their impacts are difficult to measure. Only 44% of fund managers prioritise ESG criteria in their investment decisions, while 16% take no account whatsoever.

Ultimately, without the increased data transparency needed to discover clear value drivers, the ESG performance analysis will continue to focus on whether an asset is likely to miss incoming carbon targets, or whether it showcases severe exposure to climate risk.

Split incentives

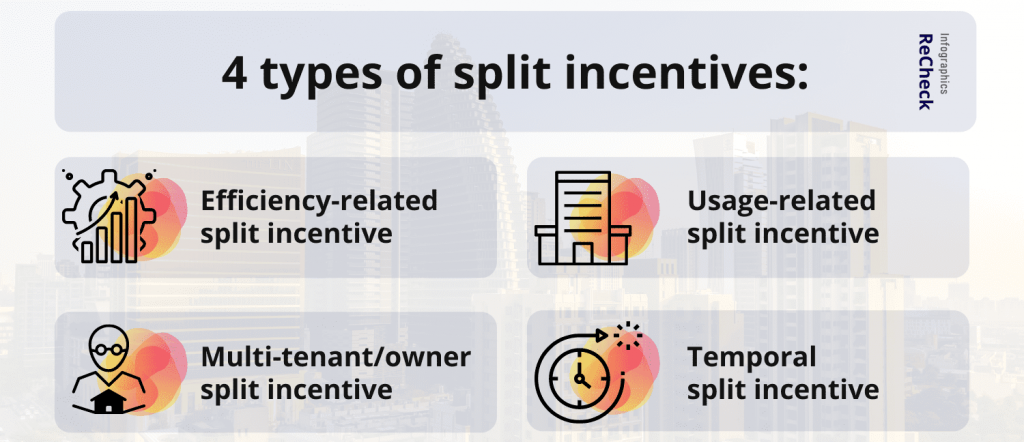

The final barrier to ESG investment is the presence of split incentives between landlord and tenant to undertake necessary building renovations. While this represents less of a data or reporting issue, it is more of a governance problem.

A split-incentive problem exists when the flows of investments and benefits are not properly allocated among the parties in a transaction, impairing investment decisions.

Due to the financial disconnect between those responsible for the investment in any operational upgrades and those who benefit from them, there is underinvestment in necessary upgrades.

There are 4 clear types of split-incentive cases –

- Efficiency-related split incentives occur when the tenant is responsible for bill payments, but not the upkeep of energy systems;

- Usage-related split incentives occur when the tenant is not responsible for paying the bill;

- Multi-tenant/multi-owner split incentives occur when decision structures act as a barrier to a collective agreement on energy-efficient systems;

- Temporal split incentives occur when the payback time of energy-efficient upgrades falls outside the tenant’s lease term.

The landlord-tenant dilemma is intensified by a lack of tenant-facing regulation to promote an occupier’s responsible energy use within an asset. This lack of occupier accountability results in assets consuming more energy in operation than it was intended at the design stage. Many operational systems continue working even when people aren’t in the building, to prevent degradation and mould.

The landlord-tenant dilemma is intensified by a lack of tenant-facing regulation to promote an occupier’s responsible energy use within an asset. This lack of occupier accountability results in assets consuming more energy in operation than it was intended at the design stage. Many operational systems continue working even when people aren’t in the building, to prevent degradation and mould.

Further governance barriers to the widespread adoption of ESG technology include the leasing process characterized by fluctuating negotiating leverage between owners and tenants. In that matter, the emergence of mandated tenant energy disclosure and standardised green lease terms would encourage the tenant to operate the property in a more responsible manner and to invest in ESG upgrades.

A new era for ESG performance evaluation and sustainable innovations

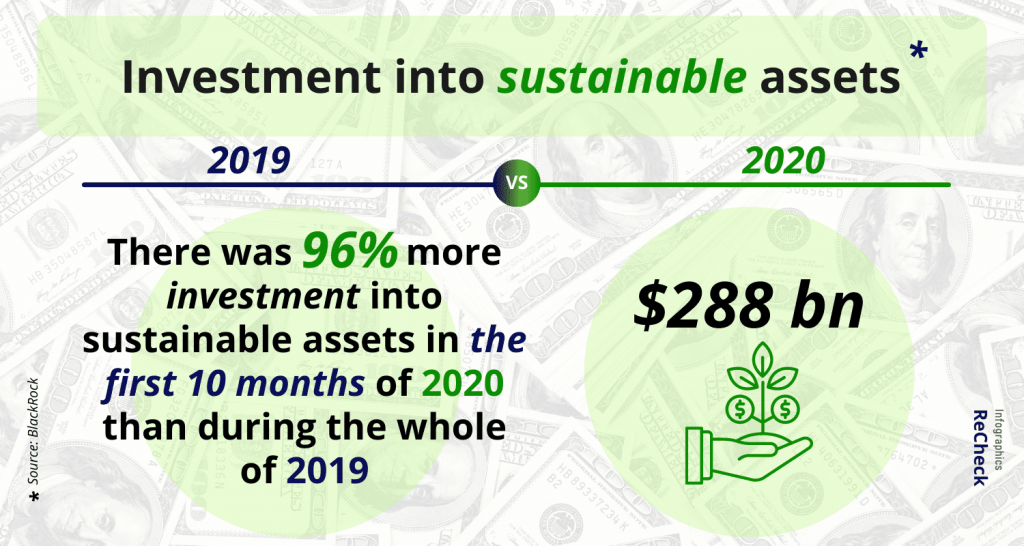

Larry Fink, the CEO of the world’s largest investment manager, BlackRock, recently declared that “climate risk is investment risk”. And as such concepts grow in importance in the global financial markets, the demand for sustainable assets will as well accelerate. There was 96% more investment into sustainable assets in the first 10 months of 2020 than during the whole of 2019. Accordingly, ESG- and climate-related funds are predicted to surpass conventional funds by 2025.

Commercial real estate companies that can confidently report strong ESG performance will be in a much better position to gain access to better, cheaper capital. According to findings from Patrizia, 72% of investors are planning to increase real estate investments in the next five years, with 9 out of 10 preparing for growing regulatory requirements and a much greater focus on ESG and risk. Furthermore, 8 out of 10 of these real estate investors has reported that they require the use of digital tools for automated portfolio analysis and reports.

In fact, using a Software as a Service platform can help automate the difficult job of data collection, while ensuring that data is accurate, secure, and accessible. That way sustainability professionals will only focus on implementing their strategies to enhance sustainability.

A study based on the ESG data compiled by the European Public Real Estate Association (EPRA) found that those firms with a greater completeness of ESG data reporting had increased returns regarding energy certification, social impact and governance scores. It turned out that the more companies report on these matters, the better their returns.

Inevitably, integrating technologies to improve data accuracy in the ESG reporting is a key step in providing greater transparency into ESG performance and revealing the value drivers required to attract further sustainable investment.

Use cases and new ESG performance benchmarks

- MIT Real Estate Innovation Lab found that effective rents in healthy buildings, defined as assets that score highly on employee or tenant well-being certifications, earn between 4.4 and 7.7% more rent per square foot than their nearby non-certified and non-registered peers.

- When put into operation at Nanyang Technological University’s 250-hectare ‘Eco-campus’ in Singapore, digital twin technology was able to generate 41% potential savings in energy consumption. (Read more)

- RESET is the world’s first data standard and certification program for the built environment. The RESET Standard creates a structure for data quality, continuous monitoring, and benchmarking, and harnesses the power of technology in order to assess the performance of buildings and interior spaces during their operational phase.

- Pioneered in Australia, the NABERS environmental rating system for offices is now likely to be adopted in the UK and New Zealand. Seen as a global best practice for measuring operational office energy efficiency, NABERS currently covers 86% of all Australian office space, leading to energy intensity improvement of 36% since the scheme started 20 years ago. In total, landlords have saved over $1bn in utility bills and 7m tonnes of CO2 since inception.

Ultimately, meeting the new mandatory criteria set by future sustainability standards will require the adoption of technologies to track, report and improve performance – technology that can deliver accurate and accountable ESG data, which will reveal transparent performance insights.